The concept of 'ma'

- Published on : 08/12/2017

- by : M.M.

- Youtube

A beauty ideal

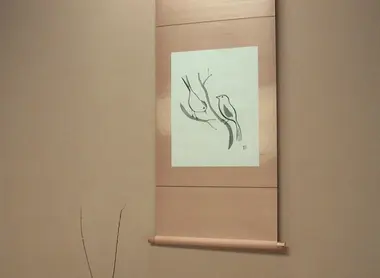

Harmony, balance, simplicity, zen... Just a few words that can come to mind when we talk about Japanese art. The minimalism can sometimes be surprising. In reality, the negative space that's left is precisely what generates their beauty. This emptiness, which isn't really empty, is the ma.

"Ma", the balance between everything

While the notion of ma is particularly present in Japanese art and aesthetics, it's also essential to understand how it affects human relations and Japanese culture. The ma is the space between two things, not considered an absence that separates, but as a relationship. Let's see a few examples to understand more clearly.

See also : Tea ceremony

In tea ceremonies, the placement of the utensils and containers have precise and complex rules. Space is divided into imaginary lines on which objects are arranged. Placing the most valuable object along the centerline is an important rule, but it must be slightly off-center. This gap, this emptiness created, is the ma. It's not the absence of something, but the heart of things. This notion applies to architecture, calligraphy, and even flower arranging.

Ma is not just a spatial concept, it's also a time interval. In Noh theater, you'll find it in the tension between two aftershocks, in the breaks that separate the actors. Again, it shouldn't be perceived as a lack or an absence. It gives a rhythm.

To read: Noh theater

The space of "Ma", a graceful shift

However, ma is not fixed. In classical Japanese dance, it is appreciated when a dancer doesn't exactly follow the tempo. A true master is able to play with times and setbacks, creating a graceful shift. Ma exists in these subtle variations - sometimes a matter of timing, sometimes a spatial shift, and sometimes even a mixture of both. But then, what place does it have in the attitudes and the human relations of the Japanese?

Each individual is compelled to adopt a social behavior. It's about controlling oneself so as not to cause shame, for example, until the ability to behave appropriately is second nature. In Japan, the logic of groups and social circles predominates. Between uchi and soto, we have the seken, those people who aren't relatives or strangers. To behave with them one can be neither too attached nor too distant, and therefore to pay more attention to the interval, to the ma , between oneself and the others. Thus, this concept is found even at the heart of interpersonal relationships.

Read also : Uchi and soto

Le ma dans les arts traditionnels japonais

Le concept de ma est particulièrement prégnant dans les arts traditionnels japonais, où il joue un rôle crucial dans la création de rythme, de tension et de beauté :

Théâtre nô : Dans le théâtre nô, le ma se manifeste dans les pauses et les silences entre les répliques et les mouvements des acteurs. Ces moments de tension et d'immobilité sont aussi importants que l'action elle-même, créant une atmosphère de profonde intensité émotionnelle.

Musique traditionnelle : Dans la musique japonaise, le ma représente les silences entre les notes. Ces pauses ne sont pas vides, mais chargées de sens et d'émotion. Elles créent un rythme subtil et une tension qui enrichissent l'expérience musicale.

Arts martiaux : Dans les arts martiaux japonais, le ma-ai (間合い) désigne la distance spatiale et temporelle entre les adversaires. C'est un concept crucial qui détermine le moment opportun pour attaquer ou se défendre. La maîtrise du ma-ai est considérée comme essentielle pour exceller dans ces disciplines.

Cérémonie du thé : La cérémonie du thé japonaise est imprégnée du concept de ma. Chaque geste, chaque pause est soigneusement chorégraphié pour créer une expérience harmonieuse. L'espace entre les objets et les moments de silence sont aussi importants que les actions elles-mêmes.

Le ma dans les relations interpersonnelles

Au-delà de son importance dans les arts, le concept de ma influence profondément les interactions sociales et la communication au Japon :

Communication non verbale : Dans la culture japonaise, ce qui n'est pas dit est souvent aussi important que ce qui est exprimé verbalement. Le ma se manifeste dans les pauses et les silences lors des conversations, permettant une réflexion et une compréhension plus profondes.

Espace personnel : Le respect de l'espace personnel d'autrui est crucial dans la société japonaise. Le ma se traduit par une conscience aiguë de la distance physique et émotionnelle appropriée dans différentes situations sociales.

Hiérarchie sociale : Le concept de ma influence la façon dont les Japonais naviguent dans les relations hiérarchiques. Il se manifeste dans la façon de s'adresser aux autres, dans le choix des mots et dans le timing des interactions, créant un équilibre subtil entre respect et familiarité.

Harmonie sociale : Le ma joue un rôle important dans le maintien de l'harmonie sociale, ou wa (和). Il encourage une approche mesurée et réfléchie des interactions, évitant les confrontations directes et favorisant le consensus.

L'importance du ma dans la société japonaise contemporaine

Bien que la société japonaise ait considérablement évolué, le concept de ma continue d'influencer de nombreux aspects de la vie contemporaine :

Design urbain : Malgré la densité des villes japonaises, les urbanistes et architectes s'efforcent d'intégrer des espaces de ma dans leurs conceptions. Cela se traduit par la création de petits parcs, de zones de transition et d'espaces publics qui offrent des moments de calme au milieu de l'agitation urbaine.

Technologie : Paradoxalement, le concept de ma influence même le design technologique japonais. Les interfaces utilisateur des appareils électroniques japonais intègrent souvent des éléments de ma, créant des designs épurés et intuitifs.

Gestion du temps : Dans le monde des affaires japonais, le ma se reflète dans une approche du temps qui valorise les pauses et la réflexion. Les réunions incluent souvent des moments de silence permettant à chacun de digérer l'information et de formuler des réponses réfléchies.

Bien-être et santé mentale : Face au stress de la vie moderne, de nombreux Japonais redécouvrent l'importance du ma comme moyen de préserver leur équilibre mental. Des pratiques comme la méditation et le shinrin-yoku (bains de forêt) gagnent en popularité, offrant des moments de pause et de connexion avec la nature.

Comparaison du ma avec des concepts similaires dans d'autres cultures

Bien que le ma soit un concept profondément ancré dans la culture japonaise, on peut trouver des notions similaires dans d'autres traditions :

Philosophie taoïste chinoise : Le concept de wu wei (無為), qui signifie "non-agir" ou "action sans effort", partage certaines similitudes avec le ma. Il met l'accent sur l'importance de l'espace et du vide dans la création d'harmonie.

Minimalisme occidental : Bien que d'origine plus récente, le mouvement minimaliste en art et en design partage avec le ma une appréciation de la simplicité et de l'espace. Cependant, le ma va au-delà de l'esthétique pure pour englober une philosophie plus large de l'existence.

Concepts de silence dans diverses traditions spirituelles : De nombreuses traditions religieuses et spirituelles, du christianisme au bouddhisme, valorisent le silence et la contemplation d'une manière qui rappelle certains aspects du ma.

Théorie de la Gestalt en psychologie : Cette approche, qui souligne l'importance de percevoir des ensembles plutôt que des parties isolées, partage avec le ma une attention à la relation entre les éléments et l'espace qui les entoure.

En conclusion, le ma est bien plus qu'un simple concept esthétique ou philosophique. C'est une lentille à travers laquelle la culture japonaise perçoit et interagit avec le monde. Comprendre le ma, c'est saisir une part essentielle de la sensibilité japonaise, une approche qui valorise l'harmonie, l'équilibre et la profondeur dans tous les aspects de la vie. Dans un monde de plus en plus frénétique et saturé, la sagesse du ma offre une perspective précieuse sur l'importance de l'espace, du silence et de la contemplation.