The Edo period (1603-1868)

- Published on : 16/04/2020

- by : S.V.

- Youtube

The era of domination of the Tokugawa shogunate

This period saw 250 years of peace thanks to a strong political regime, an unprecedented urban development, a flourishing culture and arts of exceptional refinement; this is the Edo period (1603-1868).

The Tokugawa clan came to power

Two years after the death of Hideyoshi Toyotomi (1537-1598), Prime Minister and great unifier of the country during the Sengoku era (1450-1573) or "age of warring states", the Council of Regency set-up to exercise power in the name of the young heir Hideyori Toyotomi (1593-1615) dissolves. The internal quarrels within the Council lead to a real open conflict between the Ishida clan, a supporter of the son of Hideyoshi and the Tokugawa clan led by Ieyasu Tokugawa (1543-1616) who wished to extend its domination across the whole country.

The victory of the Tokugawa clan at the Battle of Sekigahara on 20th and 21st October, 1600 marks a major turning point in the history of Japan. Nicknamed Tenka wakeme no kassen or "the battle that decided the future of the country", this one is very often considered as the unofficial beginning of the Tokugawa shogunate. However, it was not until three years later that Ieyasu Tokugawa received the title of shogun from the emperor and established a military government, the Edo bakufu.

Through skillful political maneuvers, the use of matrimonial alliances with the Imperial Family and the hereditary transmission of shogunal power, Ieyasu Tokugawa managed to consolidate his power and maintain his lineage at the head of the country for more than 250 years.

- Read also: Visit Tokyo in the footsteps of the Tokugawa

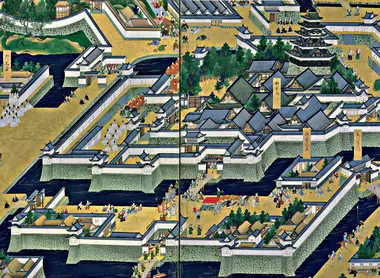

Centralized power in Tokyo

In 1603, the seat of government was installed in Edo (present-day Tokyo ) making this former small fishing village the shogunal capital and the center of political power, even if Kyoto remained the imperial capital until 1868.

From 1615, the shogun managed to monopolize all powers and spheres of influence through the promulgation of a code in 17 articles consigning the emperor to a unique spiritual and cultural role. The shogun is now the only power to manage the affairs of the country.

To further consolidate its power and curb the power of the daimyos, the great lords of provincial domains, the shogunate exercises particularly strict control against them by the sankin kotai. Came into force in 1635, this system forced the daimyos to alternate residence every other year between Edo where their family and their fiefs are installed. The costs generated by the sankin kotai (travel, maintenance costs of the double residence), were paid by the lords, are therefore a reason for any unrest.

Furthermore, maintaining order throughout the country also requires a social overhaul. The government divides the population into four rigid social classes: the Warriors "bushi" (shogun, daimyo and samurai), farmers "Nomin", artisans "Kogyo" and merchantsn"chonin". The rest of the population escapes this codification, but not under the shogunal control.

The sakoku: the closing of the country

Eager not to undergo Western influence and to control trade, the Tokugawa shogunate will gradually apply a series of isolationist measures: the expulsion of Christian missionaries following the prohibition of Christianity on Japanese territory in 1614, the ban on entering or leaving the country for the Japanese, the expulsion of foreign residents and merchants, closing of ports to non-Japanese vessels.

Thus, in 1638, the Portuguese community was first moved to Deshima an island near Nagasaki and then expelled the following year. The Dutch were also confined to Deshima in 1641; the date on which the Japanese confinement is complete. Only the trading posts of the Dutch East India Company in Deshima and a few Chinese traders in Nagasaki remain.

This isolationist policy led by the shogunate is called sakoku, literally "padlocked country".

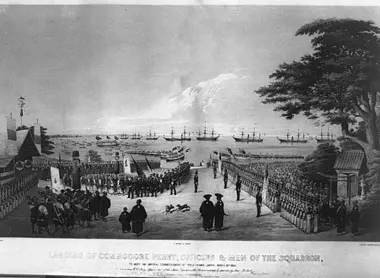

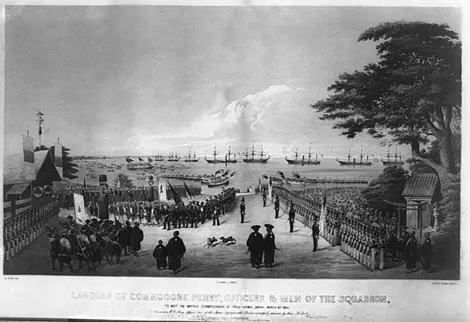

In the early 19th century, attempts by major Western nations to break this isolation are numerous. Pressure from the American Commodore Matthew C. Perry, who arrived in 1853, will get the better of the sakoku. The following year, Japan opened its borders to the United States and then to the rest of the world in 1858. The opening of the country favored the abdication of the last shogun and the restoration of the imperial power, which opened the Meiji era (1868- 1912).

The rise of Edo

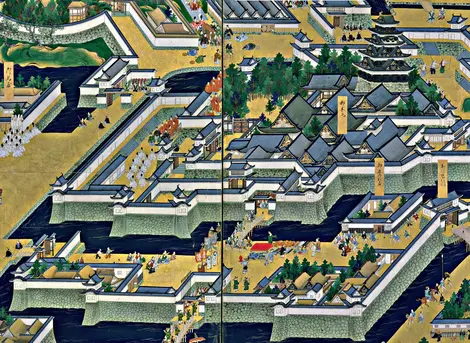

The new political and administrative regime of the country completely changes the destiny of the city: Edo.

Around the fortress completed in 1636, emerges a large and new city. Houses, shops, temples, theaters, and tea houses grew throughout the city. In these times of peace in Japan, the population of Edo is rapidly increasing. The merchant and bourgeois class take full advantage of this urban development and are profit greatly.

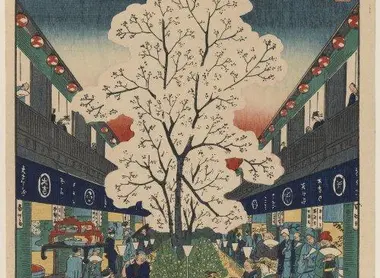

In a few years, a whole new urban and bourgeois culture, carried by chonin (merchants and city dwellers) the perpetual quest for entertainment and pleasure, was born. This has its source in the concept of ukiyo or "floating world" recorded in 1665 by the writer Asai Ryoi (1612 - 1691) in his work Tales from the floating world (Ukiyo monogatari): "[…] live only the present moment, devote yourself entirely to the contemplation of the moon, the snow, the cherry blossom, and the maple leaf […], do not allow yourself to be overcome by poverty and not to let it show through on your face, but drifting like a gourd on the river is what is called ukiyo".

The arts of the Edo period

Under the aegis of this philosophy of life, the Edo era saw the birth of arts of exceptional refinement (painting, ukiyo-e, ceramics, lacquer, sculpture, weapons and armor) and extremely popular entertainment.

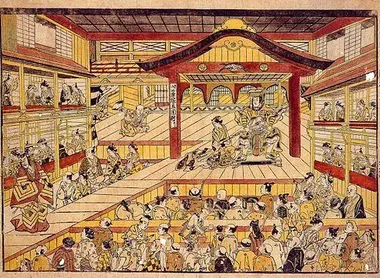

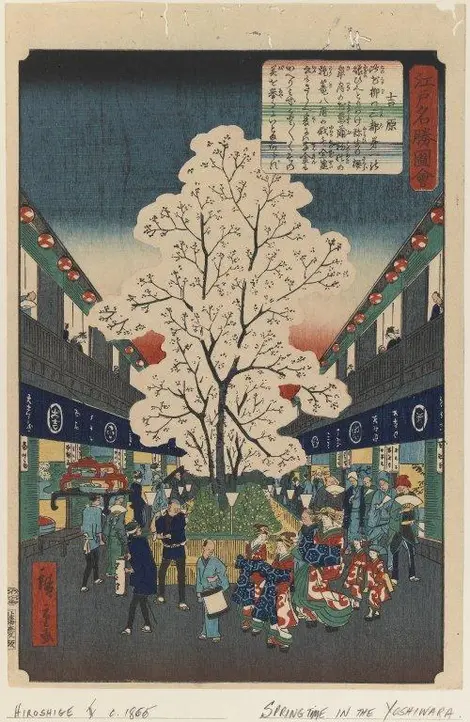

Kabuki played for the first time by Izumo no Okuni in 1603 on a makeshift scene installed in the dry bed of the Kamo River in Kyoto very quickly became fashionable throughout Japan. The city dwellers of Edo flock to the many theaters of the capital. They find fun and relaxation there as in the tea houses, restaurants and pleasure houses of the reserved area, the Shin-Yoshiwara.

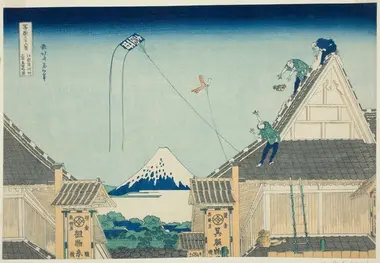

The actors and plays of kabuki, the courtesans, the beautiful young women, the famous views of Edo, Mount Fuji as well as the manners and fashions of the new bourgeois class of Edo are the favorite subjects of ukiyo- prints. The emblematic art of the Edo period. This art of woodcut polychrome knows its heyday between the late 18th and early 19th-century thanks to two large undisputed masters such as Hokusai and Hiroshige.

As for the literature of the Edo period, this is marked by the subtle poetry of Matsuo Basho (1644-1694); the grandmaster of haiku.

For further reading: