Nagasaki Christian Museum

- Published on : 02/04/2015

- by : G.L.

- Youtube

Celebrating faith against the odds

The story of the Nagasaki Christians represents a fascinating chapter in Japanese religious history, marked by persecution, resilience and faith. For over 250 years, Japanese Christians had to practice their religion in the shadows, creating a unique religious culture to survive the persecution of the Tokugawa shogunate. Today, several museums in and around Nagasaki preserve this exceptional history, offering visitors a glimpse into this intense period of Japanese history. From hidden sacred objects to poignant testimonies, these cultural institutions tell the extraordinary story of the "hidden Christians" who maintained their faith against all odds.

The history of Nagasaki's hidden Christians and their cultural heritage

The history of Christians in Japan began in the 16th century with the arrival of European missionaries, notably the Jesuit François Xavier in 1549. Nagasaki soon became the center of Christianity in Japan, with some 300,000 converts by the early 17th century. This period of openness was short-lived, however. In 1614, the Tokugawa shogunate promulgated an edict formally banning Christianity throughout Japan, forcing the faithful to choose between apostasy and hiding.

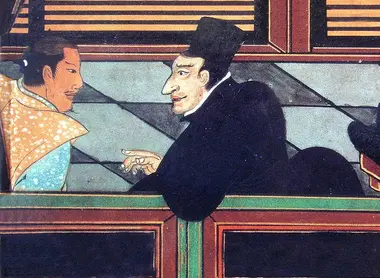

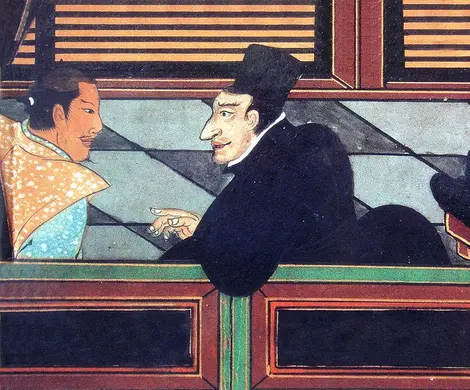

Faced with this ban, many Christians chose to practice their faith in secret. These "hidden Christians" (kakure kirishitan) developed unique practices to conceal their religion. They created disguised objects of worship, such as statues of the Virgin Mary resembling the Buddhist goddess Kannon. Prayers were transmitted orally, often modified to resemble Buddhist chants. These adaptations created a syncretic form of Christianity, blending Christian, Buddhist and Shinto elements.

One of the most striking aspects of this period was the practice of "fumi-e", where authorities forced suspects to trample Christian religious images to prove they were not Christians. Those who refused were often tortured or executed. Despite this severe persecution, the Christian communities of Nagasaki and surrounding areas, particularly on the remote islands, managed to maintain their faith for over two centuries.

It wasn't until 1873, when Japan opened up to the West, that the ban on Christianity was lifted. It was then that thousands of "hidden Christians" revealed their faith, an event known as the "discovery of the hidden Christians" or the "miracle of the East". This resurgence led to the construction of churches throughout the region, many of which are now UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Amakusa Christian Museum: main collections and exhibitions

The Amakusa Christian Museum is an essential stop-off point for understanding the history of Japan's hidden Christians. Located on the main island of Shimoshima in the Amakusa archipelago, this museum is dedicated to the preservation and transmission of local Christian history, particularly marked by the Shimabara-Amakusa rebellion.

The museum's collections include exceptional artifacts that bear witness to the underground period. Among the most notable items are those used during the Shimabara-Amakusa Rebellion, an uprising of Christian peasants in 1637-1638 that was brutally suppressed. This revolt, led by the 17-year-old Amakusa Shirô, was a decisive turning point in the history of Japanese Christians, as it led to an even stricter policy of closure of the country.

The museum also exhibits one of the world's three great religious flags, a rare historical treasure. There are also many hidden Christian relics: medallions, miniature crucifixes, holy images hidden in everyday objects, and historical documents recounting the persecutions. These objects illustrate the ingenuity of hidden Christians in preserving their faith without attracting the attention of the authorities.

The permanent exhibits at the Amakusa Christian Museum chronologically trace the history of Christianity in the region, from the arrival of the first missionaries to the contemporary period. An entire section is dedicated to the figure of Amakusa Shirô, sometimes presented as a charismatic leader, sometimes as a martyr, whose head was exhibited in Nagasaki after his death as a warning. The museum also features a reconstruction of the secret spaces where Christians gathered to pray, allowing visitors to immerse themselves in the atmosphere of those perilous times.

Other museums dedicated to hidden Christians in the Nagasaki region

The Nagasaki region is home to several other important museums that preserve the exceptional history of the hidden Christians. Starting with the Museum of the Twenty-Six Martyrs of Nagasaki, which commemorates the execution by crucifixion of 26 Christians in 1597, an event that marked the beginning of systematic persecution. Located on the hill where the executions took place, this museum displays personal objects of the martyrs, historical documents and religious works of art.

In the Urakami district, where the atomic bomb was dropped in 1945, is the museum dedicated to the history and heritage of the Christian refuge. Inaugurated in 2015 to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the discovery of the hidden Christians, this facility exhibits medals and icons hidden by Christian families during the prohibition period. The collections are managed by the Archdiocese of Nagasaki.

On the island of Hirado, the Shima no Yakata Museum presents an impressive collection of stained glass and other relics from the local Christian heritage. This island was an important Christian center in the early 17th century, before becoming a place of persecution.

In the Amakusa archipelago, in addition to the main Christian museum, there is also the Santa Maria Museum and the Amakusa Shiro Museum, which respectively detail Western cultural influence in the region and the history of the Shimabara Rebellion. In Sotome, north-west of Nagasaki, the Hidden Christians Heritage Museum illustrates how this community has managed to preserve its faith in this remote, mountainous region.

Finally, the Sakitsu Archive Center, housed in a renovated inn dating back to 1936, traces the unique history of this Christian fishing village. Unique cult objects are on display, such as an abalone tree used in religious ceremonies and handed down from generation to generation.

Historic Christian sites to visit around Nagasaki

The Nagasaki region is dotted with Christian historical sites that tell the poignant story of hidden Christians. In 2018, twelve of these sites were listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites under the title "Hidden Christian Sites of the Nagasaki Region", recognizing their exceptional cultural value.

The Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs of Japan, also known as the Church of Oura, is the oldest existing Catholic building in Japan. Built in 1864 by French missionaries, it was the scene in 1865 of the "discovery of the hidden Christians" when a group of Japanese secretly revealed to Father Petitjean that they shared his faith. This, the country's first church, has been designated a Japanese national treasure.

The remains of Hara Castle in Minamishimabara bear witness to the bloody Shimabara-Amakusa rebellion of 1637-1638. This site was the last stronghold of Christians in revolt against the shogunate, and its fall marked the beginning of Japan's period of strict isolation and intensive persecution of Christians.

The Goto Islands, particularly Hisaka Island, are home to several remarkably well-preserved Christian villages. These isolated islands served as a refuge for Christians fleeing persecution on the mainland. The Egami church on Naru Island, with its unique architecture blending Western and Japanese styles, is particularly noteworthy.

The village of Sakitsu in the Amakusa region is a striking example of the coexistence of Christianity and traditional Japanese religions. The present church was built in 1934 on the very site where Christians were once forced to renounce their faith by trampling on sacred images (fumi-e). Its tatami floor bears witness to the adaptation of Christianity to Japanese culture.

In Sotome, the Shitsu and Ono churches illustrate the rebirth of Christianity after the end of the ban. Built after 1873, they retain their original appearance and continue to welcome worshippers today.

The Shimabara-Amakusa revolt and its impact on Japanese Christians

The Shimabara-Amakusa revolt represents a crucial chapter in the history of Christians in Japan. The uprising, which began on December 17, 1637, was triggered by a combination of religious and economic factors. The peasants of the region, hard hit by famine and crushed under the weight of taxes imposed by their lord Matsukura Katsuie, rose up against shogun authority.

Although the revolt was not exclusively motivated by religious motives, it soon took on a Christian dimension. Amakusa Shirô, a 16-year-old considered by some to be a messianic figure, became the rebels' spiritual leader. The son of a Christian samurai, he galvanized the insurgents, who took refuge in the abandoned Hara Castle.

Faced with this threat, the shogunate mobilized an impressive force of almost 125,000 men. The Dutch, the only Europeans still authorized to trade with Japan, were even asked to bombard the castle from their ships. Despite four months of fierce resistance, the castle finally fell on April 15, 1638. Some 37,000 rebels were slaughtered, including women and children. Amakusa Shirô was captured and beheaded, his head displayed in Nagasaki as a warning.

The consequences of this revolt were devastating for Japanese Christians. The shogunate saw it as confirmation that Christians were disloyal subjects, liable to ally themselves with foreign powers. The policy of persecution was intensified, and Japan entered a period of total isolation (sakoku) that lasted over two centuries. The Portuguese were definitively expelled, and only the Dutch, confined to the artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki, were allowed to maintain limited trade relations.

For Japanese Christians, this was the beginning of the most difficult period. Communities had to adapt to survive, developing syncretic practices that blended Christian elements with local traditions. The figure of Amakusa Shirô became an important symbol for hidden Christians, even if the Catholic Church never recognized him as a martyr, unlike other Japanese Christians executed at the same time.

Practical information for visiting Nagasaki's Christian museums

For a complete exploration of the Christian museums and sites in the Nagasaki region, careful planning is recommended, as these places are scattered over a fairly vast territory. The ideal starting point is the city of Nagasaki itself, easily accessible by train from major Japanese cities such as Fukuoka, Osaka or Tokyo.

The Twenty-Six Martyrs Museum in Nagasaki is open daily from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., with an entrance fee of 500 yen for adults and 400 yen for children. Located in the Nishizakamachi district, it is easily reached by streetcar from the main station.

To visit the Amakusa Christian Museum, you need to go to Shimoshima Island. From Nagasaki, there are several options: take a bus to the port of Mogi then a ferry to Tomioka (25-minute crossing), or take the train to Isahaya then a bus to the port of Kuchi-no-tsu followed by a ferry to the port of Oni-ike. A total journey time of around six hours from Nagasaki. The museum is generally open from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Sites on the Shimabara peninsula, including the ruins of Hara Castle, are more easily reached by car. We recommend renting a car to explore this historically rich region effectively. The Arima Christian Heritage Museum in Minamishimabara, which presents the history of Hara Castle, is open from 9 a.m. to 6 p.m. (closed on Thursdays), with an entrance fee of 300 yen for adults.

To visit the Goto Islands, several ferries depart daily from Nagasaki harbor. Allow at least a full day, or even an overnight stay, to explore these isolated islands with their magnificent scenery and unspoilt Christian villages.

The Nagasaki Church Information Center, located at Dejima-Warf in central Nagasaki, is a valuable resource for travelers. Open from 9:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m., it offers detailed information on all Christian sites in the region, including maps, timetables and suggested itineraries.

For a more in-depth experience, consider booking a specialized guided tour or purchasing one of the regional tourist passes, which can include access to several sites and museums.

UNESCO World Heritage listing for hidden Christian sites

June 30, 2018 marks a historic date for Japanese Christian heritage. On that day, twelve sites in the Nagasaki region were collectively inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List under the title "Hidden Christian Sites of the Nagasaki Region". This international recognition crowns almost 400 years of religious and cultural resistance.

The site includes ten villages, the remains of Hara Castle and the Basilica of the Twenty-Six Holy Martyrs (Oura Church). These sites, scattered across Nagasaki and Kumamoto prefectures, illustrate three key phases in Japanese Christian history: the initial encounter with Christianity, the period of prohibition and persecution, and the revitalization after the ban was lifted in 1873.

According to UNESCO, these sites "bear unique witness to the particular cultural tradition nurtured by the hidden Christians of the Nagasaki region who secretly transmitted their Christian faith during the period of prohibition, from the 17th to the 19th century". They represent a unique form of religious syncretism in which elements of Christianity, Buddhism and Shintoism coexisted.

The origin of this inscription dates back to the mid-2000s, when a group of researchers in history and architecture set out to document the region's churches. Recognizing the importance of these buildings, they launched the idea of a World Heritage listing. After years of promotion and preparation, the Japanese government officially submitted the application in 2016.

This recognition by UNESCO has considerably raised the international profile of these sites and contributed to their improved preservation. Comprehensive protective measures have been put in place for each component of the property, in accordance with Japan's Law for the Protection of Cultural Property.

Pope Francis' visit to Japan in November 2019, the first by a pontiff since John Paul II in 1981, has further reinforced the symbolic importance of these sites. For the descendants of the hidden Christians, some of whom continue to practice syncretic forms of Christianity, this recognition represents a validation of their ancestors' heritage.

Today, these twelve sites together constitute the 22nd UNESCO World Heritage Site in Japan, testifying to the country's exceptional cultural richness and unique religious history.